CharityCAN’s Guide to Prospect Research

Prospect research is necessary for fundraising organizations of all sizes. Identifying, understanding, and connecting with potential donors – whether they are individuals, granting foundations, or corporations – is critical to the success of modern charities and non-profits. Fundraising without prospect research is like travelling without directions. If you do get to your destination, your trip was certainly more difficult than it had to be. Fundraising without prospect research consumes unnecessary resources, is less predictable, and perhaps most importantly, brings in fewer dollars.

Successful prospect research means being able to answer the following questions about your prospective donors as efficiently and accurately as possible:

- Do they engage in philanthropy?

- What are their philanthropic focus areas?

- Do they have the ability to make a gift that fits the goals of my organization?

- Does my organization have a connection to them we can use to create a meaningful relationship?

In this guide, we will introduce you to the fundamental elements of prospect research by looking at propensity, capacity, affinity, and connection.

Propensity

Propensity is the inclination or tendency to behave a certain way. As it relates to prospect research and fundraising, it refers to the inclination or tendency to make donations to charitable causes and organizations. Simply put, if someone has never given a charitable gift their propensity to make charitable donations is a quite low, whereas if someone is a monthly donor to a variety of causes their propensity to make charitable donations is quite high.

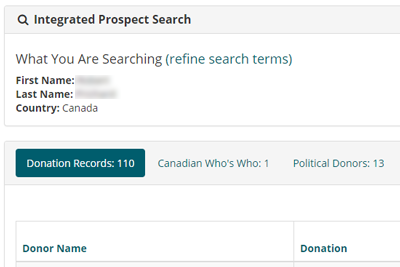

The easiest way to quickly gauge propensity is by examining donation history. This is best accomplished by examining internal donation records so you have a sense of how often the prospect gives to your organization and external donation records so you have a sense of how often the prospect gives to other organizations.

Another useful way to gauge propensity is by looking at how your prospect spends his or her time. This method is less useful with corporate or granting foundation prospects, but can be invaluable when assessing an individual’s propensity. The following questions are instructive:

- Has my prospect spent any time on the board of a charity or a non-profit?

- Is my prospect politically active?

- Is my prospect active in the community?

These questions will help determine if your prospect has the inclination to donate a valuable a resource – time – to pursuits beyond self-interest. Public service can be a powerful indicator of how an individual views his or her role in society and his or her propensity for charitable engagement.

Affinity

Affinity is best described as fondness or liking. In fundraising, affinity can be understood as a fondness for your mission or organization. If 100% of a foundation’s grants have been awarded to organizations supporting animal welfare, that foundation has a strong affinity for organizations that support animal welfare. As with propensity, donation records are great way to begin to gauge affinity.

When considering affinity, it is important to understand the difference between mission and organization. Consider the following: an individual has a donation history that is comprised entirely of gifts to her alma mater. Does this individual have an affinity for education as a cause or mission or an affinity for this specific institution? It is probably inaccurate to say she has an affinity for post-secondary education as a cause, it is far more likely she has an affinity for the place she went to school.

Capacity

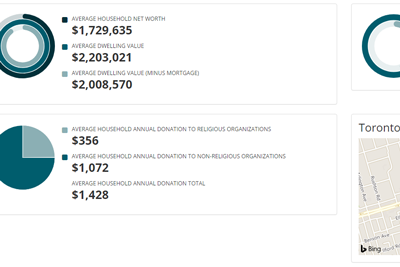

In fundraising, capacity refers to a prospect’s ability to give. Typically, capacity is measured by wealth. The wealthier a prospect, the greater the capacity to give. When looking at an individual donor, prospect researchers examine things like compensation, real estate holdings and other assets (and liabilities if possible) to determine capacity. For granting foundations, prospect researchers will look at revenue and expenses and assets and liabilities. Corporations get a little trickier, especially if private, but yearly revenue, cash, and assets and liabilities are all ways prospect researchers will determine capacity.

A major challenge prospect researchers face when determining capacity is total wealth. Unless you have access to a prospect’s entire financial history or he tells you (and you have reason to believe him), it is almost impossible to determine exact wealth.

Consider the following scenario. You are researching two prospective donors and have access to the reasonably accurate information about the market value of their homes. Prospect A owns a home with a market value of $2 million. Prospect B owns a home with a market value of $500,000. Simple enough, right? Prospect A has a greater capacity to give than prospect B. But what if prospect A has a mortgage of $1.7 million remaining on the home and prospect B paid for the home in cash and doesn’t carry a mortgage? Some of back of the napkin math shows that dwelling value minus mortgage for prospect A is $300,000 and dwelling value minus mortgage for prospect B is $500,000. Perhaps prospect B has the greater capacity after all. What if you also have compensation data for both prospects and last year prospect A received a total compensation package (salary, bonus, stock) from her employer of $600,000 and prospect B received a salary of $120,000? It looks like prospect A is back in the lead.

This example helps illustrate the primary challenges prospect researchers face when determining capacity: availability of information. Data on the market value of the properties is one piece of information that will likely paint an inaccurate portrait of the prospects’ capacity. Data on the market value of the properties plus mortgage liabilities gives us two pieces of information and our portrait starts to get more accurate. Data on property values, mortgage liabilities and compensation gives us three pieces of information and, probably, a reasonably accurate portrait of both prospects’ capacity to give.

Connections

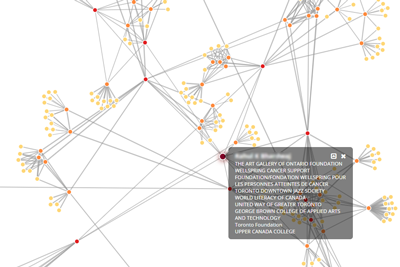

Traditionally, prospect research has focused strictly on determining propensity, affinity and capacity and supplying research and data that supports those determinations. Connecting with potential donors has been left to fundraisers. This is changing. Data that reveals organizational connections and relationships is becoming more readily available. This is helping to make relationships and connections more quantifiable than they have ever been. Compare “a member of our board served on the board of a company we would like to approach for a sponsorship from 2009-2015” versus “I’m pretty sure they used to golf together.” The availability of objective data about connections is pushing relationship research under the purview of prospect researchers.

When researching relationships, your most important concern should be verifiable data. Treat relationship data like you would donation or compensation data and look for the best data available. T3010 data (the T3010 is the tax form required by the Canada Revenue Agency to be filed yearly by every registered charity and lists the individuals on the charity’s board of directors) and management proxy circulars (securities regulators require publicly traded companies to file circulars that list key officers, executives and board of directors members) are a great place to start researching connections and relationships. Both are legal documents listing the key people at the organizations; analyzing them can help you determine – from a wholly verifiable source – who knows who and how they are connected.

A very fruitful place to start looking for connections is your own board of directors. Almost all board members have – at the very least – an implicit fundraising mandate. Also, many board members serve on multiple boards, both charity and corporate. Mining the connections of your board of directors for relationships with people who sit on the boards of large companies or granting foundations can be the difference between an accepted sponsorship, gift or grant request and a rejected one.

Conclusion

Imagine you are tasked to create a list of donors with the potential of making a $10,000 gift to your organization. First, you need to determine propensity. You can do this by examining your list of prospects eliminating those that have never made a charitable gift. Second, you need to determine affinity. To do this, eliminate the names on the list who only give to organizations with dissimilar missions or have a well documented history of only giving to a single organization. Third, you need to determine capacity. To do this, use real estate, financial holdings, and compensation data to eliminate the names on the list who do not have the capacity to make a $10,000 gift. The names left on your list are reasonably well-qualified prospects to make a $10,000 gift to your organization. Finally, research connections and relationships to determine if your organization is linked in any way to the remaining names. The names you do have connections with should be prioritized for approach. They have the propensity to give, an affinity for your cause, the capacity to make a gift you are pursuing, and connections to your organization you can utilize in your approach. They are well-qualified prospects.

Understanding the fundamental aspects of prospect research will help you direct your research more efficiently. You will spend less time chasing down information of questionable value and more time finding verifiable data that helps answer the necessary questions about propensity, affinity, capacity, and connection.